Class struggle and small circle mentality: Marxism vs. sectarianism

Date: Sunday 26th July

Time: 17:30 - 21:00 BST

In the socialist movement, there are those who compromise on political principles opportunistically in order to find a short-cut to the masses; and there those who place themselves outside the main workers’ struggle, spending their time attacking other organisations in a sectarian fashion. Opportunism and sectarianism are two sides of the same coin. Both must be combated if the programme of revolutionary Marxism is to become a mass force by connecting with the aspirations and movement of the working class. Our speaker, Claudio Bellotti, is a leading activist of Sinistra Classe Rivoluzione, Italian section of the IMT.

Audio

Video

Recommended reading:

- [Classics] What is to be done?

- Buy at Wellred: What is to be done?

- [Classics] Where to Begin?

- Marxism vs. sectarianism

- Marxism versus Sectarianism: reply to Luis Oviedo

Transcription

Claudio: Good night everyone here. I will start with a short quote from a letter Karl Marx wrote in 1871.

“The International was founded in order to replace the socialist or semi-socialist sects by a real organization of the working class for struggle. The original statutes and the inaugural address show this at the first glance. On the other hand, the internationalists could not have maintained themselves if the course of history had not already smashed up the sectarian system. The development of the system of the socialist sects and that of the real workers’ movement always stand in inverse ratio to each other. So long as the sects are historically justified, the working class is not yet ripe for an independent historic movement. As soon as it has attained this maturity, all sects are essentially reactionary. Nevertheless, what history has shown everywhere was repeated within the international. The antiquated makes an attempt to re-establish and maintain itself within the newly achieved form.”

In this letter, Marx referred to the First International and the internal struggle between socialists and anarchists that ultimately ended with the dissolution of that organization. And many times, starting with the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels criticized those communist and socialist tendencies, schools and sects that preached socialism and their particular recipe for rebuilding society according to justice. And that was the infancy of the workers’ movement, where the working class had not yet developed its own independent organizations and its aspirations and its needs were mainly expressed through the propaganda of the utopian socialists of different shades. In that sense, the struggle to move forward from that embryonic stage can be considered won, and that stage has been overcome since long.

It is true that with the fall of the Soviet Union and the ensuing ideological reaction, many mass movements saw a revival of utopian ideas about how to overcome the evils of capitalism. That was particularly evident in the so-called anti-globalization movement in the early 2000s. But those ideas were generated not in the working class, but in the petty-bourgeois sectors which tried to figure out a way to resist the crushing pressure of finance capital. But sectarianism reappeared, as Marx wrote, in a new shell many times along the history of the working class and the revolutionary movement.

It will be easy to list some of the features which characterize sectarian tendencies and organizations. The one-sidedness, for instance. The tendency to accept only some forms of the class struggle. There are sects for instance who consider that only strikes are a real proletarian form of struggle, denying any other activity as opportunistic. Or groups that dedicate themselves exclusively to propaganda, disassociating it from any activity in the movement.

In 1935, Trotsky dealt with the question of sectarian tendencies inside those forces that were trying to build the Fourth International. And it was not the first, nor the last time that he had to write on this. Here are some passages from this article:

“Every working class party, every faction passes during its initial stages through a period of pure propaganda, i.e. the training of its cadres. The period of existence as a Marxist circle ingrafts invariably habits of an abstract approach to the problems of the workers’ movement. He who is unable to step in time over the confines of this circumscribed existence becomes transformed into a conservative sectarian. The sectarian looks upon life in society as a great school with himself as a teacher there. During a certain stage of development, rationalism is progressive.”

I am cutting down the quote.

“The progressive stage of rationalism is repeated in every great emancipatory movement. But rationalism, or abstract propagandism, becomes a reactionary factor the moment it is directed against the dialectic. Sectarianism is hostile to dialectics not in words, but in deeds, in action, in the sense that it turns its back upon the actual development of the working class.”

This is Trotsky in 1935. And this approach, he was talking about, often presents itself in a negative form, that is, the demonization of this or that form of struggle – be it the parliamentary struggle, the economic struggle, and so on – with the promise that if the movement stays away from them, it will be free from the danger of opportunism and degeneration. And all these mistakes, and many others, show a clear trait of idealism and subjectivism. They try to build their own working class, their own workers’ movement, instead of standing and intervening in the real class struggle, by taking reality as a starting point and not any principle invented in a closed room.

However, I would warn against a discussion that sets off from a mere list of sectarian traits or features. Like any other political phenomenon, sectarianism is rooted in the class struggle. It is not enough to find a definition of it and to apply it to a given tendency to find whether it fits or not into it. This approach is only a first step, but being purely static, it cannot show the objective roots and development of that particular phenomenon.

Like some of the older comrades here, I had been a member of the CWI, the Committee for a Workers’ International, which was a Marxist organization that degenerated into a sect. And that was due both to objective and subjective reasons I will touch briefly later on. That was an example of sectarianism which came about as a part of the defeat of the working class internationally. The defeat of the workers’ movement at the beginning of the ’80s of the last century. But history shows us other and different examples.

In the founding years of the Communist International, Lenin and Trotsky had to wage a very serious and principled battle against the sectarian tendencies in the newly formed Communist parties. That was particularly true for the German and the Italian Communist parties, but others as well, like the British. In that case, the sectarian tendency manifested themselves among sectors of the working class, and specifically of its vanguard. That is, revolutionary workers and militants who had been repelled by the betrayal of the Second International during World War I, and galvanized by the Russian Revolution, reacted vehemently against the Social Democracy. They rallied to the Communist International which, by the way, explicitly appealed to ultra-left and semi-anarchist tendencies like the French syndicalists, the Spanish CNT or the IWW in the U.S., they appealed to join ranks with the Communist International.

That was absolutely correct at that time, as the sectarian traits could be overcome with a combination of principled and democratic discussion and the living example of the mass revolutionary movement that was developing. Lenin’s masterpiece “Left-Wing” Communism and many documents and speeches from the 2nd and 3rd Congresses of the International reports the truths of that battle or that discussion. A big emphasis was put on explaining the need to sink roots in the trade unions to win the majority of the working class to the revolutionary programme and perspective. To make good use of all the different fields of activity in order to build the revolutionary party. And the question of the united front was at the core of these debates, as well as the question of the workers’ government or workers’ and peasants’ government, according to the different countries.

The underlying idea can be synthesized this way: that in order to reach the masses that still follow the reformist leaders of the Social Democracy and the trade unions, it is not enough just to appeal to them to leave their organizations and join the revolutionary party. It is necessary to address their leaders in order to reach their members. It is necessary to put before the reformist leader precise demands for united action, to reach the masses over the heads if you like of the reformist bureaucracy. This approach was rooted in the experience of the Russian Revolution between February and October 1917. At that time, the Bolsheviks as a tiny minority in the soviets openly appealed to the reformist leaders, inviting them to take power. In the same way, in August 1917, they applied a united front tactic to fight Kornilov’s attempted coup. And that tactic was absolutely essential in order to prepare the October Revolution.

And of course, the united front is not a panacea to be applied always and under any circumstance. As Trotsky remarked, it would have made no sense for instance to appeal to the reformist leaders to organize the seizure of power in October. As I said before, the ultra-left tendencies were strongly present in the Third International at its inception, and the Bolshevik Party itself was not immune from this tendency in 1919. The idea of a communist leap was present not only among the left communists, that is Bukharin and others.

In 1921, at the 3rd Congress of the Communist International, Trotsky honestly explained that in 1919, there was the hope that capitalism could be toppled in Europe by a single assault, that the revolution could storm and conquer in a sweep all of the continent. But despite the great revolutionary élan, the revolutionary situation in Hungary, in Bavaria, in Italy and so on, the events gave proof that in order to win the revolution in Central and Western Europe, a deeper preparation was needed, and that the Communist International had to seriously undertake this task if it was to fulfil its historical task and not to degenerate into a sect.

In a certain sense, we could say that those sectarian tendencies were a healthy reaction which reflected the growing radicalization of the best vanguard of the working class. They could be corrected and in many cases they actually were corrected from the infantile disorder, and that was Lenin and Trotsky’s approach. And Lenin clearly stated that even too often, the ultra-left mistakes were a retribution for the opportunistic sins of the reformist bureaucracy.

Therefore, in order to understand, it is not just a question of finding a definition of sectarianism, good for all times and all circumstances. But we must rather understand the process. The working class is not a monolith, is not homogenous. Different economic conditions, different experiences will give rise to different political consciousness.

There is also the pressure of other classes, like the lower strata of the petty-bourgeoisie or semi-proletarian sections of the working class, which under certain objective circumstances can become very active and develop a confused anti-capitalist consciousness. This is certainly true in the present epoch, when the crisis of the capitalist system destabilizes and threatens their conditions of existence. The so-called populism which puzzles the progressive intellectuals must be explained firstly by this objective basis. This movement, and I am referring to those petty-bourgeois movements who are more or less confused on the left, certainly have an influence on the working class, particularly when the class is not mobilized, and they can create a fertile ground for impatience or hope in miracles and adventurist trends in minority sections of the working class.

In the trade union movement, you also witness many times the emergence of ultra-left tendencies to split away from the mass trade unions. This phenomenon did arise from different material basis. Sections of the working class can find themselves in a particular condition that pushes them to act independently from the general movement. In most cases, this is a combination of objective and subjective factors. The trade union bureaucracy often act as a block for the organization of a given layer of the working class, particularly amongst the most oppressed and the most exploited sections. Agricultural labourers, for instance, very often immigrants, living in a very precarious existence, are seen with suspicion, are kept segregated by the reformist bureaucracy. And in many countries, they give a point of support for independent trade unions.

In Spain, the SOCs, the Sindicato de Obreros del Campo, which later evolved into the SAT, is a good example of these militant and fighting trade unions. These fighting trade unions which can actually become majority unions in a given section, in a given industry or region, while being a minority in relation to the labour movement in general. Historically, the Industrial Workers of the World, the Wobblies in the US, are a good example of this. This has always been connected to the subjective action of political cadres from left-wing and sectarian organizations.

In some industries and trades in different countries, we see similar developments. In the logistic delivery industry, for instance, we see many examples of this sort of organizations. The fast growth of these industries through the e-commerce in recent years give a certain bargaining power to the workers, while the official trade unions quite often are incapable of reaching these workers and to confront giant companies like Amazon, United Parcel Service and so on, when they are not directly in the pocket of the management, which is often the case.

In this regard, the phases and documents of the first Congresses of the Communist International are compulsory reading for all of us. The Communist International clearly stated that active and organized work inside the mass reformist trade unions was a duty for every Communist party, and no exceptions were allowed. And it warned against the splits that separate the most advanced layer from the mass of the class, thus facilitating their isolation and repression, both from the bureaucracy, the bosses and the state.

At the same time, the Communist International stated that this formula was not to be turned into a dogma or a fetish. In those cases where the bureaucracy actively and effectively blocked the organization of the section of the workers, the setup of independent trade unions was considered as an option, provided that it was understood by the workers and that a united front tactic was consistently employed and applied towards the majority trade unions.

History shows that these militant and minority unions never develop beyond a certain point. And when they reach that limit, they lose their worker base and turn into ossified sects or disintegrate. And the only answer lies in the theoretical and political approach to these phenomena. Quite often, these more radical unions are influenced by another distortion, that is a tendency to confuse economic and political struggle. And just like they hope to bypass the obstacle of the reformist bureaucracy by setting up a separate union, they hope to solve the question of the political leadership of the proletariat by using these unions as a substitute for a political party.

This conception has a clear anarchist or anarcho-syndicalist origin. But at times, it has been adopted by cadres of Marxist or semi-Marxist background. So it is absolutely essential for us to discuss the relationship between the economic and political struggle, both in general and at every concrete turn of the event. And as well as the relationship between the different layers of the working class and their mutual connections. Only through this constant theoretical training we can effectively intervene in this field, build a fruitful relation with these struggles, and fight to avoid that good working class fighters are lost for the cause when the limitations and the mistakes of this strategy become apparent. At the height of the mass movement, the consciousness tends to be more homogenous. When the formerly backward strata rise up and catch and even sometimes overlap the vanguard, and the presence of a working class revolutionary party can be the decisive element to bring this consciousness to the necessary level in order to face the historical task of the conquest of power.

But this is the exception, because under capitalism, the normal condition is of much more discretion, difference and even conflicting tendencies inside the masses. And it would be yet another sectarian mistake to believe that a vanguard organization can change this through mere propaganda, or even through action. The revolutionary party or tendency in these epochs has the task of carefully analysing at every juncture, under any given circumstances, the state of the movement, to spot those progressive tendencies that manifest themselves amongst the masses, and try to connect to them in order to advance its cause.

Sectarian or ultra-left groups did in fact play a role also in mass movements, as witnessed by the example of the ’60s and ’70s in several countries. Italy was one clear case, but not the only one. There are those who refer to revolutionary movements like the Cordobazo in Argentina in 1969, and many, many others. And in a very general way, we could say that most of the ultra-left tendencies in those years were, originated amongst the students. And the radicalization of the youth in the second half of the Sixties was certainly an anticipation of the process going on deep beneath the surface of society inside the working class. It was like the radicalization of the Russian youth before 1905 Revolution. And that was also fuelled by international events, and in this sense, it was also distorted by the particular form that the colonial revolution took in the post-war period.

The Chinese Revolution, and in particular, the Cuban Revolution, the guerrilla liberation war in Vietnam, were seen by the revolutionary students as a new perspective for the revolution. And of course, the perspective of a peasant guerrilla could not appeal to the working class in Europe, and it led to tragic experiences and the deform of a revival of terrorism at a later stage. But before that, that generation of students did actually play a role in the big movements, not only in the schools and universities, but in the working class too.

There were also some cadres who had broken with the Communist and Socialist parties earlier, who played a leading part in those movements between 1968 and ’69 in Italy. And for a short while, paradoxically, their sectarianism, their ultra-leftism gave them an advantage on the trade union bureaucracy. They maintained a lot of awfully wrong ideas, and a wild spontaneism above all. But this found an audience in the big industrial plants. The most exploited layers of the working class, most of them of recent immigration from Southern Italy, were suffering from low wages, discrimination inside and outside the workplaces, and savage exploitation on the assembly belt during the post-war boom. And they were largely neglected by the trade union bureaucracy and gave a good response to the students coming at the factory gates with revolutionary propaganda.

And so they discussed jointly with the students the conditions, the demands and what to do. And actually, there was a stage in 1968 when the ultra-left groups were in a position to command an important following and to call effective strikes in some of the biggest industrial plants in Northern Italy. And the tragedy that they did not have the theoretical arsenal to understand what they were in effect doing. The unbroken thread, this is the unbroken thread of Marxist theory, was not present and it had been cut previously, in particularly by the role of Stalinism.

Had they had a real Marxist grounding, history could have taken a different path. It was the ultra-left sects were in effect able to organize several thousands of young workers and students, maybe 30,000 as an overall figure at their peak. And the biggest groups had 5,000-8,000 each, which was a small force compared to 1.5 million or more in the Communist Party, but still could have played a different role. And with an adequate tactic towards the trade unions, to factory councils and the Communist Party, they could have laid the basis for a building of a small revolutionary party. Just like the Biennio Rosso group in Turin in 1919, 1920, was able to win the best workers’ vanguard in the factory councils, which later gave an important base in the working class to the newly formed Italian Communist Party in 1921.

Unfortunately, the ultra-left in the late ’60s did not possess this sort of theoretical armoury. They proclaimed the death of the trade unions, they boycotted the newly formed factory councils, they glorified the purely economic demands on wages as inherently revolutionary, and so on. And so on, and so they facilitated the comeback of the trade union bureaucracy in the following stage.

In more recent years, there were other examples of the sectarian organizations acting as a sort of barometer of bigger events to come. I have in mind the example of the Argentinazo in 2001, the insurrection that overthrew five presidents in a couple of weeks after the financial collapse of the country. That was a key link in the chain of revolutionary events which in that decade spanned from Venezuela to Bolivia, Ecuador, and in one way or another, touched most of the Latin American continent.

A few months before that explosion, the left, which in Argentina for historical reasons has always been composed by important sects, mainly with Trotskyist allegiance, had an unexpected result in the polls with an overall figure of 10% or so of the votes. But as I said, it was mainly a symptom of a deeper process which expressed immediately after in a full-scale insurrection and a revolutionary situation. It is important to notice that despite this relatively important role, the sects in effect denied the perspective of a revolutionary, of a revolution and of workers’ power. They relied on electoral tactics or cultivated their own points of support in very specific sections of the masses, like the unemployed of the Piqueteros movement, for the Partido Obrero or some of the occupied factories of the PTS, which went through all the main groups.

Of course, it is absolutely correct to intervene energetically amongst those sections of the working class that display fighting ability. Our Brazilian section, for instance, has a proud history of supporting and leading the struggle in occupied factories run by the workers themselves. The mistake of the sects was in giving an absolute value to a specific movement, to figure it as the working class movement and the only one. To mistake the part for the whole, if you like, and that leads inevitably to mistakes of both ultra-left or opportunistic nature. And that revolutionary situation gave life to a discussion of workers’ power. And Alan Woods’s article that was included amongst the readings for this session deals precisely with that discussion, and why some groups like the PTS tended to minimize the scope of the movement, referred to it just as “revolutionary days” and not a revolutionary situation.

Others, like the Partido Obrero, spoke of a revolutionary situation, but did not draw the necessary strategy from that, and evaded the decisive point using the confused slogan of the Constituent Assembly. And in the following years, electoral policies and tactics became more and more dominant, leading to a serious problem of adaptation to the bourgeois state and of watering down of the program and subsequently to splits and crises in these groupings.

The same contradiction became an advanced layer and the mass of the working class I referred to in relation to the early years of the Communist International, can also emerge in an inverse form, if you like, like in a mirror in different circumstances. When a mass movement develops, it generates thousands or tens of thousands of new activists and new cadres, but as people who overnight embrace the active participation in the movement joining its organization, people who are leaders of the masses. But when the movement begins to ebb, this layer will not necessarily be able to understand the change immediately and to act accordingly.

The process is well explained in Trotsky’s analysis of the 1905 Revolution and it’s also dealt in detail in Alan Woods’s history of the Bolshevik Party. In 1906, 1907, the movement in Russia was retreating after the bloody suppression of the Moscow uprising. But while the masses were slowly retreating, a layer of the vanguard had drawn revolutionary conclusions from the experience of 1905, and joined the ranks of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, both the Menshevik and the Bolshevik wing. And this explains the fact that during the retreat, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party reached its peak membership, as registered at the Congresses of 1906 and 1907.

This contradiction too gave rise to sectarian tendencies inside the Bolshevik faction, such as the boycott of the elections and a semi-terrorist deviation amongst a layer of the Bolshevik activists. Some of the leaders of these factions like Bogdanov always had some sectarian traits and theoretical differences with Lenin. But under different conditions of 1904, 1905, these were not a real danger. But in the new situation, Lenin understood that the sectarian mistakes combining with the negative turn of the objective situation could be a mortal danger for the Bolshevik tendency, and could condemn the Bolsheviks to a sectarian degeneration.

And that is why, while previously Lenin tolerated them, although without making the slightest theoretical concession, now he went for a head-on clash. And that included both a political battle, for instance on the question of participation in the elections and legal activity in general, and also a theoretical backlash against the philosophical idealist tendencies that lay at the bottom of this ultra-left faction.

We can say that in epochs of retreat and defeat, it is almost inevitable that part or even the majority of the revolutionary movement degenerates in sectarian forms, as it is just not possible to reach the masses. The fate of the Fourth International was set by the defeat of the late ’30s and the ’40s which gave the reformists and the Stalinists an iron grip on the labour movement on a world scale, in segregating the masses to the side-lines for a whole historical period. When similar developments come about, there is room for all sorts of mistakes, notwithstanding the amount of Marxist phraseology and quotes which are written into political resolutions or leading articles on the party press.

A key text that should be carefully studied by all communists is the Program of the International, written by Ted Grant in 1970. In that document carefully traces the theoretical roots of the degeneration of the Fourth International and its capitulation to the adverse historical forces. I’m not going further on that as I think that the session on the history of the IMT will deal with it in-depth.

On a much smaller scale, the sectarian degeneration of the CWI in the mid and late ’80s had some similar traits. The general trend after the ‘70s was one of retreat of the working class internationally. And in Britain, the Militant had attracted thousands of dedicated fighters who had drawn conclusions from the ’70s, particularly about the limits and betrayals of reformists, and also of left reformists. But at the turn of the decade, the workers’ movement began to suffer a series of important defeats, like the miners in Britain, or the Fiat workers in Italy in 1980, and the defeat of the Left Coalition government in France. The defeat of the air traffic controllers’ strike in the US in 1981. There were many of these defeats, both on the economic and political front. And that turn clashed with the previous experience, and so the contradiction expressed in the CWI and the Militant, this idea that you could advance in the same way under any objective circumstance by applying organizational pressure on the organization.

Now, retrospectively, we characterized that epoch as one of mild reaction. But even in epochs of retreat, the processes are not homogenous. There will be cross currents. In the mid-late ’80s, the CWI was able to intervene and even to lead mass movements, like the anti-poll tax movement in Great Britain, or the student movement in Spain in 1986-87. And while these were stunning successes, there was also a great danger entailed, which only later became apparent, because it is all too easy in such circumstances to mistake one particular trend which is moving forward for the general and prevailing trend, which at the time was moving backwards, a mild reaction, as I said.

For peculiar reasons, as more organizations can find itself at the head of a mass movement, and of course it is duty-bound to fulfil its role as best it can. But this does not mean that that position is won permanently, nor it means that that particular movement sets the main trend in society. Missing this point was one of the causes that contributed to the sectarian evolution of the CWI and had effects on a section of our Spanish cadres later on.

There were several other sides to that process – I can’t deal properly here, but one is worth quoting. Participation in the mass organizations in itself is not a guarantee against sectarianism. The Militant was a part of the Labour Party, but this did not prevent its sectarian evolution. In fact, the fact it commanded the majority in the Labour Party Young Socialists at a certain point contributed to the bureaucratic tendencies which were linked to that method of administrative pressure I referred to.

There was a certain layer of so-called cadres who had emerged mainly not from the participation in the movement and in the building of the underground, nor for their political and theoretical contribution, but rather by advancing along internal lines in the organization. And that increased the tendency to an authoritarian method of leading, which proved to be a fatal weakness when a few years later, the organization was not prepared to have a real debate. They seemed to turn in the world situation in 1989 and 1991. And this sort of sectarianism had nothing progressive, nothing infantile in it. It was rather an ossification, and all the attempts to fight it through a serious internal debate proved futile, as a position led by Ted Grant, Alan Woods and others was simply expelled in a few months.

Parallel is with the splits Ted Grant had to cope with in the late ‘30s or in 1949 or in 1955 with the so-called Fourth International. Despite Ted’s persistent attempt to discuss and to overcome the differences with a principled debate, that was not possible. And in all those instances, the only way the Marxist tendency could survive and re-establish itself was through a split. But in all these historical examples, Ted’s method which we have to defend was to debate and to defend the principles, amongst which the question of internal democracy was not the least important.

That is the Leninist method, and it is important to notice that in 1906, Lenin was prepared to remain in a minority amongst the Bolsheviks, accepting the boycott of the elections although he was against it. Even more noticeable, the fact that Lenin and Trotsky on the eve, just before the Third Congress of the Communist International in 1921, contemplated the hypothesis to be in a minority given the strength of the ultra-left tendencies of the German and Italian Communist parties in particular. They were firmly convinced that discussion, even an internal fight, combined with experience would show the correctness of their stand and overcome the sectarian mistakes.

And I am quoting these episodes for an important reason: because the IMT today is a homogenous political organization, and this was won through discussion and theoretical training. But we have entered an epoch of catastrophic events, an epoch of unprecedented crisis of capitalism, of intense class struggle, of revolution and counter-revolution. And these events will test us too. We will have to face new problems, changes, sharp turns, and this will inevitably create differences and even political conflicts. And not to think so would amount to embrace the wildest form of idealism and detachment from reality.

As materialists, we base our actions on the objective situation as we can understand it, we know that our program, our strategy do not come just from our desire. But this has nothing in common with a fatalistic optimism, or a passive contemplation of an objective development. The October Revolution was the result of the objective reality of the class struggle in Russia and on a world scale. But it became a reality only through the will, the subjective action of the Bolshevik Party and its leadership. And in the same way, the building of a new revolutionary international is an objective necessity, but it is a subjective act that depends on the collective action of men and women who choose this endeavour.

I have not dealt with the conditions of the sectarian galaxy these days because the crisis is complete. It is not by chance, it is part of the preparation of the world-shaking events that are in the making, and these groups are part of the past. And the surest symptom of their crisis is that in many countries, they try to join forces to build united fronts amongst them and so on. Our general relationship with that world is the same we had in 1938 or 1960, ’65. “Go your way ’til the end, gentlemen, and we will ignore you and face to the working class.” We face the youth and the best representatives of those millions, of those billions of people who are facing the decay and rottenness of capitalism and will fight to find a way out.

There is a passage in the Programme of the International I mentioned by Ted Grant, which I think illustrates the relationship between those two elements, the subjective and the objective, in an unsurpassed way. This is my last point, comrade chair. And I quote: “The pressure of capitalism, reformism and Stalinism in a period of capitalist upswing in the West, the temporary consolidation of Stalinism in the East, the perversions of the colonial revolution as explained in the preceding material, of Stalinism, were the causes of the degeneration of all the sects claiming to be the Fourth International. But an explanation is not an excuse, and necessity has two sides. In preceding history, the degeneration of the Second and Third Internationals due to objective and subjective factors did not justify the leaders who had abandoned Marxism. It did not justify either reformism or Stalinism. Similarly, there is no justification for the crimes of sectarianism and opportunism which have been committed by the leaders of the so-called Fourth International for more than an entire generation.”

Comrades, Ted Grant was never afraid of calling things by their right name. Already in the ’40s, he referred to the sections of the Fourth International as small sects. And at that time, that included the RCP, of which he himself was the main political leader and theoretician. It was a sharp way to warn of the danger that even promising revolutionary organizations can fall into the blind alley of sectarianism and being lost to their historical task.

Today, this gigantic task lies before us. The historical trend is once again moving forward, and we must therefore assume full responsibility for that, and I’m sure that this discussion and this school as a whole will be an important step. Thank you, comrades.

Interventions

Erika: Thank you, Claudio, for introducing this topic. I agree a discussion cannot be about merely naming characteristics of sectarianism. The historical examples Claudio gave are important to study. The political organizations and parties which made sectarian mistakes also have many positive lessons we can learn from. We are focusing on the mistakes in this discussion in hopes of avoiding them ourselves.

The Bolsheviks also made sectarian mistakes. The party which was new and more accustomed to small circle propaganda work did not want to get involved in the apolitical soviets which had emerged in 1905. Only after Lenin’s repeated intervention from abroad did they reluctantly try to appeal to the workers in the soviets. But by then it was too late. There was no trust built between the Russian socialists and the workers and peasants in the soviets. The Bolsheviks would often get kicked out of the soviet meetings or not allowed to speak. They had cut themselves off from the masses, from the very working class that they had sworn to lead and serve.

This is the consequence of sectarianism. The Bolsheviks, thanks to Lenin, were able to overcome and correct this mistake. “We do not shut ourselves off from the revolutionary people,” Lenin said, “but submit to their judgement every step and every decision we take.” Several years and revolutions later, he was able to advise young communists in Germany and Britain about the dangers of the sectarian approach in “Left-Wing” Communism, an Infantile Disorder.

In particular, he argued against the developing tendency in young communists to abstain from electoral politics altogether. They were arguing that parliamentarianism or bourgeois democracy is politically obsolete, and to participate in it would be to become opportunist or corrupt themselves. We understand that we will not be able to simply vote away private property and capitalism. A revolution is necessary. And in this sense, communists understand bourgeois democracy as historically obsolete. But it has not yet proved itself to be obsolete to the entire working class.

Lenin says, “Whilst you lack the strength to do away with bourgeois parliaments and every other type of reactionary institution, you must work within them because it is there that you will still find workers.” In other words, if you cannot yet offer the workers anything better, you must use the same institutions through which the working class channels their energy: the institutions which presently actually exist, not the perfect mass revolutionary party which only exists in the mind of the sectarian.

Lenin directly advised the young British comrades to call on the workers to vote for Labour against bourgeois parties. To use this election in 1920 as a platform to put forward a revolutionary program. But how do we apply this advice in the USA, a highly developed country with still no labour party? The absence of a labour party in the US does not mean that the working class has no illusions in electoral politics. They do not see electoral politics or bourgeois democracy as politically obsolete. In the US, there exists a vacuum in political leadership for the working class. But nature abhors a vacuum. The movement around Bernie Sanders which first emerged in 2016 came out of this vacuum.

Yesterday, Jorge Martin talked about the radicalization of younger generations who came of age during or after the 2008 economic crisis, who have only known instability, austerity, impending climate catastrophe and seen mass movement after mass movement. This is the context in which the movement around Bernie Sanders emerged. His program offered reforms American workers desperately needed: a public health care system, free education, reforms that at this stage capitalism cannot provide even in the richest country in the world.

We needed to connect to the working class at the level of consciousness it had reached. However, to encourage any illusions that the working class could win these reforms by working in a capitalist party would be a mistake and a lie. We engaged with Sanders supporters at rallies, events, expressing our support for these reforms, and we called for reforms that went farther than Sanders was willing to go. We also explained why Sanders running as a Democrat crippled the struggle for these basic reforms. We did not compromise on the idea that the workers need political independence from the bourgeoisie.

The day Sanders announced that he was suspending his campaign, we got over 100 submissions to our website. The method we used in order to arrive at this orientation to the Sanders movement was the transitional method. The transitional method is the result of applying Marxist philosophy, dialectical materialism to the concrete task of building a revolutionary party. I’ll wrap up since I only have a little bit of time left.

Dialectical materialism is the philosophy of change, as the working class is not a monolith and develops non-linearly. Sectarianism finds itself disconnected from the living, ever-evolving working class because it does not base itself in dialectical materialism. It is one thing to quote Lenin and it is another to apply the same method to different conditions. We are here to study the ideas and the method of Marxism to lead the working class to fulfil its historical role. And we are here to arm ourselves against any method that undermines this effort.

Joel: Well, thank you Eric, thank you Claudio for the great presentation.

I think this question of sectarianism and sectarian attitudes is very important for Marxists today, because if we look at the Marxist movement and Marxist organizations, they have never been so disconnected from the masses, that if you went back 100 years or even less in many countries, there was an organic link with Marxism and the masses, or at least the advanced guard of the masses – that most people in the labour movement, at least the activists, would have been some form of Marxist or socialist or revolutionary.

But this link has been severed for many reasons. Marxist groups are generally speaking small circles, small study circles on the margins, on the edge of the movement. And it’s been this way for some time. And this is important to note because, this situation comes with dangers, that being isolated from the masses for an extended period of time, you can develop sectarian prejudices, and actually be hostile to the real development of the working class, because it doesn’t fit exactly with what you read in a book, for example.

This was the case with the Bolsheviks in Russia, actually, as Erika mentioned, who actually demanded that the soviets in 1905 submit themselves to the party. And you see modern examples of this attitude in I think most Marxist groups or Marxist attitudes towards the Jeremy Corbyn phenomenon in Britain. Claudio mentioned the CWI, which in Britain basically refused to join and participate in this process, which is a process of millions of people, which, we obviously have our criticisms of Jeremy Corbyn, but to refuse to join the Labour Party at this time and actively be engaged with the Corbyn supporters is just sectarianism.

So Marx famously said that the emancipation of the working class must be the working of the working class itself. But the working class doesn’t come onto the scene politically, spontaneously with a perfect Marxist programme, but comes to those conclusions through a long and painful struggle, trying out this or that leader or party. It’s been mentioned Jeremy Corbyn, Bernie Sanders, SYRIZA, France Insoumise. And overall, the masses don’t learn from reading Marxist theory like we do, but they learn through experience.

So many, many, many people now – I’d say millions of people – have learned the limits of reformism. But not because revolutionaries denounced these people, but through the actual experience of reformism. Erika mentioned Bernie Sanders, the betrayal of Bernie Sanders twice now. And in Britain, Jeremy Corbyn’s refusal to fight the right reformists, which has led to the situation we have now in Britain.

But I think we will see many, many formations similar to the ones mentioned, which don’t have a perfect Marxist program for us, but are expressions of this mass discontent of the working class. And we cannot simply reject these out of hand, as many people do. We must seek for a way to connect the advanced revolutionary conclusions of Marxism with this process of development of the consciousness of the masses, which is inherently contradictory. Without a flexible approach, a successful revolution is actually not possible, because the sectarian, non-flexible approach rejects the process of development of the consciousness of the masses, which effectively makes Marxist ideas unable to reach the masses.

So to sum up a bit of what I think our approach is: so we don’t do what sectarians do and mistake our consciousness for the consciousness of the mass of workers. We don’t get frustrated that most workers don’t agree with Marxism, which is actually quite common on the left. But if you’re actually a Marxist, you would say, “Of course they don’t agree with Marxism – yet.” Because Marxist conclusions are hard to swallow, and people don’t arrive at them overnight.

So as Lenin said, we must patiently explain as we have been patiently explaining that it was a mistake that Bernie Sanders was in the Democratic Party. And we patiently explained all of the errors that Corbyn was making. So we must develop a flexible approach without abandoning our principles, because that would be the other danger, which is opportunism. So we must find a way to connect with the masses, their movements, their organizations, as they come into being, change and evolve as the masses learn – and we should be confident and optimistic, because we have the benefit of Marxist theory, which helps us see which way things are going, so we can be confident that the events will prove correct our perspective, and the masses will come to our side. Thank you.

Casper: I’ll do what Claudio said we shouldn’t do. I’ll try to make a list of the differences between Marxism and sectarianism, because I think it helps me to think about it in a clear way.

I think the first difference is that we Marxists, we have an unabridged faith in the possibility of consciousness to change and on a mass scale in the relatively near future. We live in a period, in a moment when people realize that they cannot continue living like they did before. And people don’t change habits or ideas easily or voluntarily, and I include myself in this. But the crisis forces people to do that.

I live in Switzerland and there’s a reason why people here still have illusions in capitalism and the whole regime, some illusions, because the system could give them a more or less stable life for a certain period. But Switzerland is not isolated from world capitalism, and so the same processes are at work here, just a little bit delayed. And if you have been to only solidarity demonstrations with the Black Lives Matter movement, you feel that consciousness has already made a huge leap, especially with the youth. And this is only the beginning. And it’s a perspective of massive changes in the near future and the potential for revolutionary ideas. That is the main difference between Marxists and sectarians today.

The second difference I think is that it’s the huge events that people experience around the world that is destroying old ideas. It’s not thanks to us. And these ideas get smashed because they don’t correspond to the world we live in today. And this is mostly an objective process that happens independently of us, and is not in our control. But the central question is actually, what do these ideas get replaced with, and how fast? This is our job and our responsibility, and I think this is the main discussion we’re having here.

The third difference is that sectarians have a static view of the relationship of forces, and we have or we try to have a dynamic one. We make the same observations sometimes, for example, that today most people aren’t revolutionaries yet. And this observation that no doubt people aren’t revolutionaries, it’s true, but it’s not the whole picture, because the decisive feature of our epoch is that new layers get thrown into the fight and get politicized and draw radical conclusions on a daily basis.

And so consciousness will change exponentially, and not gradually. And this is our chance. But the question is how to prepare. And one main question is, what do we do with the advanced layers, the one who arrive at revolutionary conclusions first? Should they substitute the masses because they arrived at these conclusions first, or should they turn towards the masses? And I think one main point is that only because the advanced layers have already understood something, for example that parliament is a useless institution in our fight, we should not give in to their radicalism because this would be opportunism. But we must explain to them that behind them are thousands who are on the same track, on the way to discover the same truth, but who have not yet arrived there.

And an important part of the process when radical ideas reach the whole masses is that the advanced layer must orient to the rest, to the second layer or the advances, and make sure that they come to the same conclusions as fast as possible. And for this, they should not isolate themselves, which is a real risk, as Claudio explained for example with the small unions.

And the [fourth] difference is the consciousness that workers in struggle actually often come to the same conclusions as Marxists, but from another angle. As Joel said, they don’t learn from books and theory, but from experience, experience which is often painful and cruel. And so they can and do draw revolutionary conclusions from their experience, but this takes a lot of time. And to speed up this process is one of the main reasons for the existence of a revolutionary party, that we defend openly a revolutionary programme, a programme that actually is just the accumulated experience of the working class for the last 200 years.

And the way we defend this programme shows the difference in approach, because the slogans and demands with which we intervene in struggles or strikes or political fights, these aren’t ready-made, finished recipes for struggle. In our approach, we apply the method of transitional program as Erika explained. We do propose slogans and demands to help struggle. But we need to prove that these demands and these slogans are efficient and useful, and with this we prove ourselves the usefulness of Marxism.

But we’re not economists or syndicalists. We don’t want just to help out because we’re friendly. This would actually be opportunist. We always draw the attention to the limits of partial struggles that at best can win partial, temporary victories. But we don’t do this in an arrogant way, not with the aim to demoralize. This is a fine line to sectarianism. But we are always honest and we tell the truth, that basically under capitalism, there are no lasting solutions for our problems.

And I think a fifth difference is the focus we put on education in Marxism and theory and method, because for us, it’s not enough to be “on the left” or to unite everybody together. If we want a real unity, a stable and powerful unity, we need to unite on a set number of ideas and principles. Otherwise, it’s an opportunist unity that breaks down at the first onslaught. So if we staunchly defend our programme, it’s because we’re proud to have a programme and to have a method, to have a set of ideas that can give real answers to the most pressing problems of humanity. Opportunists of all shades, including sectarians, call this principled stance sectarianism because we defend our programme. But it is not. It is political honesty.

And for a sixth difference, in Switzerland, the main hobby of sectarians is to burn and vandalize bank offices at the back of the demo from a minority position. And we don’t criticize this from a moral standpoint, but from a standpoint of method. Banks are our class enemies, or the bankers. But it’s actually not true that the Swiss workers don’t understand that, especially after 2008 and maybe for the first time, bankers were not seen as a national pride anymore in Switzerland, but as something despicable.

So I say Marxists are not in the business of vandalizing bank offices, especially not the Swiss Marxists. We know that our historic task is to expropriate these banks, and to give back the stolen profits and super profits to the workers of all the countries where the money comes from. And this is not only a necessary, but a realist task. But it’s not for us, it’s not for our organization alone to accomplish this as a substitute for the class. And it’s only the Swiss working class that can and will do this. But for this, the conscious need for revolution, Marxism needs to find a road to the Swiss workers. And to accomplish this, we need to avoid sectarianism or opportunism, and that’s what we dedicate all our work into, and if we accomplish it, nothing can stop us. Thank you very much.

Pedro: Hello comrades, thank you for the high-level discussions in the school, I’ve been learning a lot.

Well, Lenin wrote in What is to Be Done? that a Marxist’s attitude should be to help from within the workers’ movement to bring the socialist consciousness to the class struggle. But how to do it? In One Step Forward, Two Steps Back, two years earlier, he said the party had to delineate its boundaries between what would be itself, and what would be the working class as a whole. This certainly did not mean separating itself from the working class movement, like the illuminated ones. But rather, it means to create a combat and a professional organization capable to help workers to seize political power in a favourable moment. History proved Lenin was right. The workers cannot seize the power alone without a socialist consciousness. Therefore, the party of the vanguard proletariat.

However, Lenin’s proposal was denied by the new reformists who emerged after [inaudible] of Social Democracy, and also by the ultra-leftists. Along the 20th century all over the world, the leadership of the parties with thousands of workers inside accepted all kinds of bourgeois ideas and ramifications. They defended the existence of new vanguards, saying that the working class is no longer the same, and said we cannot repeat formulas of the past, and so on. A lot of them enjoyed in recent days in the progressive internationally, headed by Bernie Sanders and Yanis. The ideological [inaudible] varies between the vanguard workers and the bourgeois was destroyed.

On the other hand, the reformists took advantage in their propaganda of the emergence of various political organizations that behaved like sects, self-proclaiming the truly Fourth Internationals, they truly were the parties of the revolution, and waiting the masses to understand who was the true leadership. But the leadership of working class can only converge itself in the fight. The leftists, instead of being the most conscious parts of the workers’ movement [inaudible] it started to highlight itself in the movement as its most revolutionary party. Being the most revolutionary party of the workers’ movement was not what Marxists advocate in this fight.

The International Marxist Tendency must have patience with, continue to feed a spirit of combat, where each comrade inside must act as part of a combat and professionalized organization, with the aim of intervening inside the workers’ movement, blending socialist consciousness, but not separating the communists from the liberals as it were. Like Marx’s words, I will read now:

“The Communists are on the one hand practically the most advanced and resolute section of the working class parties of every country. That section which pushes forward all others. On the other hand, they have over the great mass of the proletariat theoretically, the advantage of clearly understanding the line of march, the conditions and ultimate general result of the proletarian movement.”

Thank you comrades. Long life to the IMT and the working class movements! Death to the capital, its governments and defenders!

Sum up

Claudio: Thank you very much to all the comrades who contributed to this discussion. I must say that the condition of most of the sectarian groups and organizations, I would say all around the world maybe, there are exceptions, but I don’t know important exceptions, is really unprecedented – an unprecedented crisis.

Thirty years ago when I joined the movement, or 40 years ago, a sectarian was an ultra-left, was mainly a young student or a young activist, impatient, calling for revolution every day and maybe clashing with more experienced, older or even sceptical workers, maybe linked to the Communist or Socialist party. And most of them were very active, very energetic, maybe they burned out their energy in a short pace of time, but they were always present.

I look around today. Most of the sects, not to say all of them, are old organizations of old, demoralized people whose main activity is to find excuses to do nothing. This is certainly the case in Italy, but I’m sure that in most of the countries comrades could confirm this. And far from preaching revolution next Monday at 8 o’clock in the morning, they all are very well-versed in the argument to explain why revolution is not possible, neither today nor next Monday nor next year. And in this sense, they are absolutely on the same ground as the bureaucracy, in this scepticism and in this complete mistrust in the working class and in the class struggle.

So when Comrade Hamid called me a couple of months ago or one month ago asking me whether I could prepare this discussion, I thought I did something bad, I was going to be punished to deal with such a sorry subject. And in this sense, I think there is a parallel, also on a moral and a general plane, with the situation I referred to of 1938, with Ted Grant and the Fourth International.

If the comrades read the very good book, The History of British Trotskyism, and the related political documents of those years, they will see that at that time in Great Britain, all the different Trotskyist groups merged in order to become the official section of the Fourth International in Great Britain. But since the fusion was completely unprincipled, Ted Grant and a very small group, maybe 30 comrades, refused to participate. They were prepared to be in a minority, provided that the fusion was principled on clear positions that could be challenged and discussed in the following stage. But since it was a very rotten compromise, they stayed outside.

And in the stage of three or four years, history showed that the Workers’ International League – that was the name of the group that Ted Grant and Jock Haston were leading – became the strongest organization in the Trotskyist movement at that time in Britain, while all the other groups collapsed.

Where is the parallel with that today? First of all, these sects were based upon the old generation mainly, and Trotsky himself explained that a generation who is defeated is doomed, if you like, is defeated in the class struggle and also the organizations that that generation builds upon its own shoulders will collapse or will degenerate anyway, and that was the case of all these groups.

Second, and this is very much relevant today, all the reformist organizations were completely mixed with a national government because of the war, the national coalition, and their internal life was completely destroyed. There was no life whatsoever because of the war, again, and so there was no mass environment to work in for revolutionaries. And that involved those of the trade unions, by the way.

Thirdly, there was an enormous pressure on the working class because of the war and the crisis, and this is the case again today, of course in different conditions for different reasons. And so there was a wide gap between what the working class was experiencing and the absolute impossibility to express this experience and its struggle through the mass organizations, the trade unions, the Labour Party in that case and so on, and the absolute need for revolutionaries to find their own way.

Of course, they knew, Ted Grant and his comrades knew that they were a very small organization, that they couldn’t lead the masses, they couldn’t even reach the mass of the working class. But nevertheless, they systematically worked towards different industries, towards different areas of the country, with the aim of establishing first the roots and first links with the working class. When they reached a certain strength and even were able to absorb some of the remnants of the other groups, they decided to call themselves a party – I think they had 600 or 800 active members and several thousand sympathizers. And so despite being such a small force, they correctly understood the task of that day, of that stage, and in a sense they were sectarian towards the sects, and they were not sectarians towards the class.

And of course, there are a lot of differences with that stage and this is not a perspective discussion, but certainly the main difference is the demise and the defeat of Stalinism internationally, which at that time was a very strong obstacle. And reformism also today is moving on a very shaky ground, on very thin ice – the reformist bureaucracy particularly, the left reformists.

So I would say that today, the danger of sectarianism doesn’t come for us, for the movement in general, from these leftovers of the old left and ultra-left organizations, which are really no more than an appendage of the reformist bureaucracies, they just pandered to these bureaucracies, tried to find some room, some place here and there. I think the more serious discussion we could have about the danger of at a certain stage, of impatient mood and maybe some adventurist trends in mass movements like Black Lives Matter, or maybe in Chile or other countries which experienced recently an insurrectionary situation.

I can guess that since these movements cannot achieve victory in a short space of time, maybe in some layers, there could develop at a certain stage some adventurist trend, and that’s why I refer to the sort of healthy sectarianism, I mean, that ultra-left moods which come out from genuine fighters and genuine movements. But precisely because it’s genuine, it’s also dangerous, because it is related to the real movement and can lead to serious mistakes, so we must identify and engage these tendencies when they present themselves on the scene.

And in this sense, I must say that one of the most important counterweights to the danger of sectarian tendencies or ultra-left tendencies for us too is a systematic work towards the working class, towards the factories, the workplaces, the trade unions also, although I must say that going to the working class doesn’t just mean going to trade unions. But we certainly must take on board the rule of the Communist International that a communist organization must strive systematically to establish points of support in the economic organizations of the working class, that is, the trade unions – to be recognized as a legitimate part of that movement and a voice to be heard.

And during the pandemic, we experienced in Italy, but I’m sure again that this is also the experience of other comrades, that in the workplaces, every comrade, any comrade could find an audience amongst these or her colleagues, discussing the question of security, of the lockdown, how to deal with the health, the danger for the health of the working class and so on. Any comrade, even the less trained, you didn’t need to be a shop steward, a political cadre, you could just speak out our position and get an audience.

And precisely in these conditions, we show that handing over, I mean, giving the responsibility to the oldest comrades to act and to discuss amongst themselves was a great tool, a great lever – not only to build our forces, but also to raise the political, the general political level and to ensure that all of our debates were very closely linked to the real mood in the class, and not to be distorted or deviated by subjective ideas or ideas elaborated in our closed flats where we were living during lockdown.

And it is absolutely true what several comrades said – I’m referring to Erika and Joel and other comrades maybe, that new mass movements will come out in the next stage due to this pressure from the masses. And we could say that the last wave of this movement, the left reformist movement, theories of Corbyn, of Melenchon, of Sanders, several others, suffered a very deep and fast defeat in the last months. And I think that in Spain, Podemos is on the same track and moving quite fast. And this confirms an old law that we always explained, that the right-wing reformists are in their own way consistent. They cling to the state, to the ruling class, they know what they are doing, they are prepared to do it at any cost, while the left reformists are much more inconsistent and incoherent.

But since the masses have no way out, they will create new movements and new leaders in order to find some solution, and certainly we will have to work and to orient towards these movements in the ways that comrades indicated. But certainly, I will say that these phenomena are much more unstable and short-lived than in the past. They do not have the same rules that the left reformist tendencies had in the ’70s or in the ’60s, and I think that while we will have of course all the methods that the comrades explained in order to approach these phenomena, the key point in order to not just to follow them, is that we are able to establish ourselves as an independent voice in the movement, as a part of the movement, as a legitimate part of the mass movement, but with a very clear profile, with a very clear political identity, which is what we are doing now – because it is true that we have only once to understand that these movements are a partial, distorted and unfinished expression of the class struggle or the class contradictions.

And for the sectarian, all these phenomena do not exist. They are not linked to the class struggle, because in their head, the class struggle is only what they consider such, or if it doesn’t fit to the model, it is not a real class contradiction and doesn’t exist. And since it’s quite late, I would like just to finish on one point.

I spoke about the young revolutionary students in Italy, or that was the case in France or in many other countries in the Sixties, in ’68 or ’69. And when you read the reports, the memories and the books written – some of the books at least – written on that epoch, it’s really moving in some ways, the way they threw themselves towards the working class, seeing it as points of support that could give force to their revolutionary aspiration.

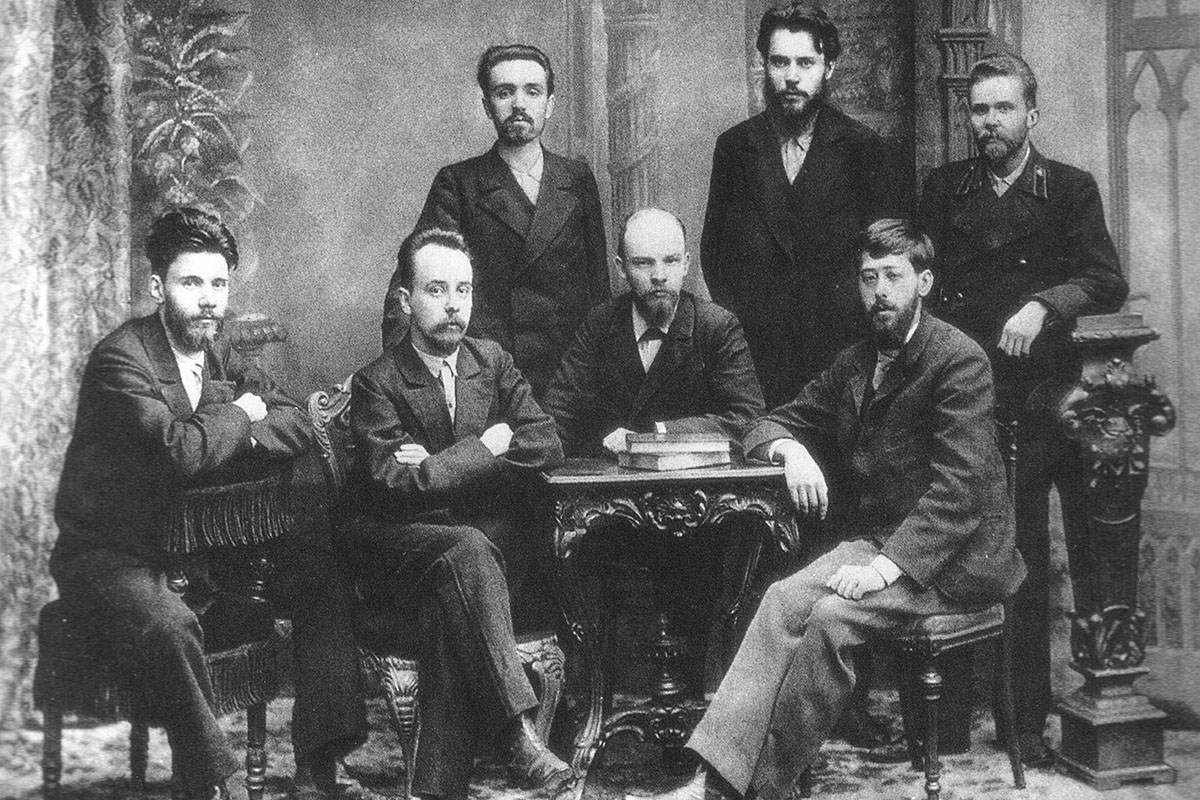

And if you go even much more backwards in time, it would be beginning of the Bolshevik party, of the Marxist movement in Russia, we see something similar. Maybe the comrades had heard, or they can read in the wonderful history of the Bolshevik party by Alan Woods, of the “going to the people”, when the populist revolutionaries, young students, went amongst the peasantry, and they didn’t go only amongst the peasants. A section of them went towards the factories, including Plekhanov, who was in charge of the trade union or workers’ or factory work of the populists at the time. And the spirit, the revolutionary spirit was absolutely the same that we need today.

They didn’t have any Marxist theory to guide them, to give them a leading orientation. On the contrary, they had a whole host of wrong theories. And those in the ’60s and ’70s, those students, at best had some caricature of Marxist ideas, but they were actually completely confused by Maoism, by guerrillaism, by some sort of Stalinist faction and so on.

And today, it is not by chance that the IMT is approaching and attracting so many young people – students, school students, and in general young people – in most of the countries. This is certainly a testament of the good work our comrades are doing, but also a sign of the general process which is going on.

We will continue this. We will deepen this, and we will have our own “going to the people”, which will be a going to the working class. And this time, it will be, with Marxist ideas, with a Marxist programme, with Marxist tactics, and it will not end in any abortion, in any ultra-left movement, but it will end by building a real mass revolutionary party all over the world. Thank you, comrades.